Digital healthcare has never been more urgent. Especially in Ireland. About one in four Irish people, around 1.3million people, currently linger on a healthcare waiting list. This July, 627,856 people in Ireland waited for a first outpatient appointment. This is 4,000 more than the month before. And there have never been so many of us, not since before the Famine.

Thanks really to advances in healthcare, Irish life expectancy increased 2.5 years in the last decade and a half to 82.7 years. Our 5.1million population is the highest since the 1841 census. On top of this, hospitals in Ireland are still dealing with Covid-19 (on September 15, 2022, there were 236 coronavirus cases in Irish hospitals, not so far down on 292 a year before), plus a growing number of patients who deferred procedures during the pandemic.

So hence, really, the need for digital health. Making hospitals run more efficiently and digitally is the best hope going for reducing waiting lists. And providing patients, especially ageing ones, with more of their care at home.

Female surgeon using digital tablet of hospital

Get it in binary

But before hospitals can bring artificial intelligence and precision medicine to bear on treating their patients, first they have to digitise their data. We have hospitals “still treating patients on paper in 2022,” marvels Raphael Jaffrezic, who is chief information officer of Blackrock Health Galway Clinic, a private hospital which since 2022 is part of the Blackrock Health group. And all too often, Irish hospitals are among them.

“90 per cent of all hospitals in Ireland are mainly paper-based,” he says. “We are hugely, hugely behind.” Part of the reason, he adds, is elsewhere – from the US to the NHS in the UK – there have been financial incentives to digitise, and in America, even disincentives not to.

In fact, it’s an “extremely and well-known incentive from the US”, Jaffrezic says that “after a deadline, you have to pay the government a certain amount of money every year if you’re not digitised.” But if you’re a hospital in Ireland “it’s do it at your own cost and whether or not you think it’s a good idea or not a good idea” he says.

Raphael Jaffrezic from Blackrock Health Galway Clinic

And “they are very long programmes, they are big transformational projects. They are hugely beneficial but you really want to be hungry for that sort of project,” he adds. There are glimmers of hope, though, says Jaffrezic. The New Children’s Hospital will have fully digital patient records when it opens, and at the other end of patient care, a majority of GP surgeries are digitised.

Meanwhile, the Mater Private hospital network, with flagship hospitals in Dublin and Cork, has just announced it is investing €26million in a new digital record platform. GP practices “are their own little businesses, so being digital does save them money in the long run, instead of storing all those paper records and keeping track of everything,” he says.

Use your silicon noggin

Once hospitals have their patient data in digital format, though, they can “get into the really cool stuff,” says Jaffrezic. Clinical decision support systems, descended from early experiments in the 1980s, were originally thought of as algorithms to make decisions for a doctor. Now they are thought of instead as AIs to help make a better analysis of a patient’s data than either a human or AI could make on their own.

Another important contribution? It is easy for a doctor about to prescribe a medication to consult a list of other medications that interact badly with it. But many hospital patients are on multiple prescriptions. So how can you tell if three medications might interact badly, even if none of the three pairs do? “AI can very much go through that amount of overall patient data, and discover interactions that appear when you start to prescribe three or four or five medications,” says Jaffrezic.

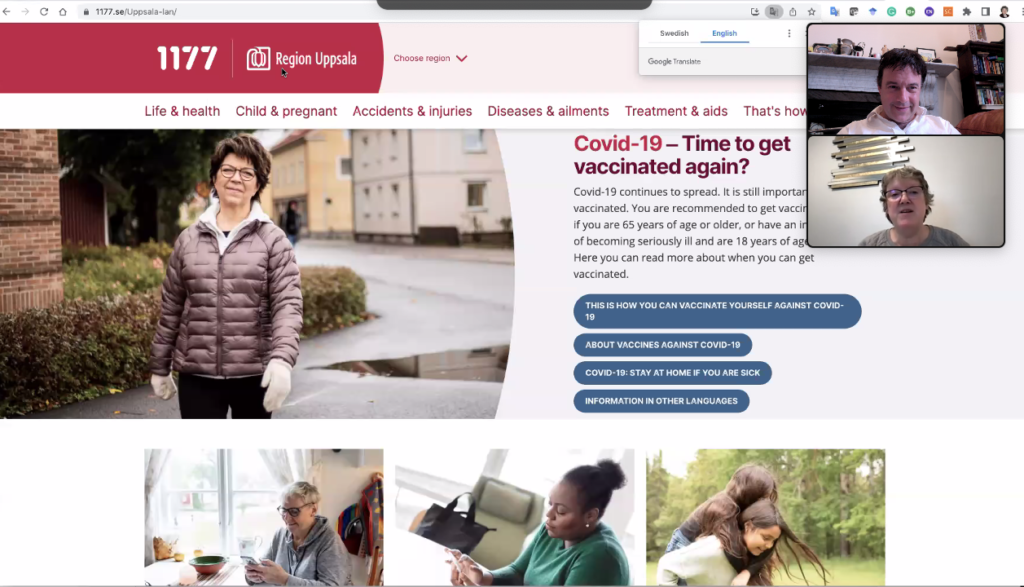

Bridget Kane showing the Swedish health information portal to SmartHealth reporter Pádraig Belton

If Ikea made hospitals

Sweden has emerged as one of Europe’s leaders in the digitisation of hospitals, after several ongoing government initiatives in e-health and the standardisation of information in healthcare. The country has several, mostly private, providers of digital health services, along with digital platforms which healthcare providers can use to create their own.

“The key to the process working is everybody has a unique ID,” says Bridget Kane, a Trinity College Dublin graduate who is now an academic at Sweden’s Karlstad University, and whose research specialises on medical information technology. She compares it to the Irish PPS or the UK National Insurance number, but with a difference.

“That ID carries you everywhere – even the supermarket loyalty scheme has the same ID. Privacy is very different, they don’t think anything of that,” says Dr Kane. So while Scandinavian countries have solved the technological challenges of digital healthcare early, they have solved it in a particularly Scandinavian way.

“I think it’s important to emphasise there are cultural differences between populations,” she says. Digitisation “started in Upsala, around 2018, and rapidly spread out to the three regions of Sweden,” she adds. Patients have access to “quite a lot of information here” about their tests and bloodwork, she says, while displaying in her own patient portal, a graph of her haemoglobin levels over time.

Andy Bleaden, community director of the European Connected Health Alliance Group

One thing cropping up, she says, is “people want to put in their own data, from their Fitbit or heart rates from their running machine.” Another debate fought in Sweden, ultimately in the courts, is whether psychiatric records also should be included in the patient portal. “There is a lot of research ongoing, whether it is beneficial or not for patients to be reading about their own diagnosis.” Though it may be a more complex question than that. “I think in some instances it might be good and in some not helpful,” Dr Kane adds.

Another anomaly is the age at which control of children’s patient data is handed over from their parents to them. Currently there are two years where children’s data is private from their parents, but they themselves do not yet have access to it – so in that two year window, apart from healthcare professionals, no one has access to their data. While there are distinctive national approaches, there are also EU laws ensuring some measure of consistency across the 27 member states.

One EU law says all citizens in the European Union should be able to view and share health records digitally by 2030, from public and private hospitals to nursing homes, pharmacies and GP surgeries. In Ireland, the Health Information and Quality Authority, Hiqa, has called for a national body to ensure this will happen for Irish patients. The Irish digital health care landscape is “under-developed” says Rachel Flynn, its director of health information and standards.

“This can lead to repeated tests and delays in care,” she says. We can work it out The “biggest headache are silos” which patient information lives in, but can’t jump across, says Andy Bleadan, community director of the European Connected Health Alliance Group (ECHAlliance). While these used to be between organisations, “now in the digital age they are within organisations and teams,” Bleadan says. “They were there when I started in healthcare in 1990. They are worse now,” he adds.

Research meanwhile shows a big cause of problems in healthcare lies in communication failures and information not being transferred properly between teams, agrees Dr Kane. And by using digitisation, “if we could get that right, I think we could get a lot of improvement overall for patients,” she says.